|

|

How To Set Up Debian Linux Internet Servers

The material on this page was prepared using

Lenny which only includes Apache 2.2.

For our page which covers configuring Apache 1.3

on Etch or Sarge, click here.

While Linux/UNIX can be used as a workstation OS it's real power shows itself when used as a server. The lean structure of Debian allows even an old Pentium III system to operate as a server. And the fact that Web (Apache) and e-mail (Sendmail) server applications are free and included with Debian, once you've set up a Debian system all you have to do is install the Apache and Sendmail packages and you're in business.

On this page we'll show you how to set up the two most common types of Internet servers. A server running Apache to act as an external (Internet) or internal (Intranet) Web Server, and an e-mail server running Sendmail which is the most widely used e-mail server software on the Internet. Note that this is not an either/or proposition. You can run Web and e-mail server services simultaneously on the same system.

It's not really accurate to categorize Web and e-mail servers as "Internet servers". Web servers are often used for internal intranet sites and most organizations have internal mail servers so that co-workers can e-mail each other. So while these servers could also be categorized as "LAN servers", we have them on this page because they are the two most common types of Internet servers.Setting up the Web and e-mail servers is only half of it. Without DNS services no one will be able to get to them. On the DNS page we showed you how to set up DNS services using either your own server or a third-party, including the free dynamic DNS service that you can use for home and test servers.

If you want to set up a serious Web server you'll want some kind of scripting capability. The Apache install sets up CGI (Common Gateway Interface) automatically. With CGI the code that gets executed are stored in separate files on the server in a cgi-bin directory. With CGI you can run plain-text scripts that get compiled into an executable each time they are run, such as with Perl scripts, or they can be pre-compiled executables written in a language like C. The big advantage of CGI scripts is that, because they're stored in individual files, there are literally thousands of free CGI scripts available on the Internet that you can download and use on your Web sites. You don't have to learn how to program in a given scripting language to take advantage of scripts. For more information on CGI and Perl, see our CGI/Perl tutorial page.

Another approach to Web scripting is to embed the script code in the HTML documents. This is the approach taken with PHP, Microsoft's ASP, and ColdFusion and you have to learn how to program in these languages to use them. (When you're surfing the Web you'll often see Web pages in your browser's location line with extensions like .php, .asp, and .cfm which indicates the pages were written with this scripting approach.) The Web server parses pages with these extensions, picks out the embedded script code, and executes the script code before sending the page to the browser. Any results of the script execution are displayed in the page at the same location the script code is located in the HTML document. This scripting approach is the desired approach for Web developers who wish to have their Web pages access back-end databases.

Installing Apache on a system and not having associating with a domain name can also be valuable. Such a system can serve as a development or test platform when you're writing new Web pages so you're not testing out new pages on your production Web server.

A Note About Windows Web Servers

Back on the Linux Basics page we outlined the cost differences in setting up a Linux Web/E-mail server vs a Windows Web/E-mail server ($20 vs $14,680 for 100 users). Some may feel they're tied to the Windows platform because they have a significant investment in ASP Web page development.

Good news! There's a package from Sun called JSASP (formerly ChiliASP by Chilisoft) which will allow you to run ASP pages on Apache Web servers.

Back on the Networking page we mentioned that if you plan to set up a serious, high traffic (read "thousands of page views a day") Web server you'll want to have a symetrical broadband connection to the Internet with a static IP address. However, if you just want to set up a Web server to host one (or even several) small Web sites you can do so using your home broadband connection and a dynamic DNS service (which we show you how to do on the DNS page). Just keep in mind that when you do this you open up your system to traffic from all over the world and there are a lot of hackers out there, so be sure to harden your Web server before going live (see the Security page for more information).

Most of the applications that run on servers are "daemons" (pronounced dee-mons). Daemons are applications that run in the background, waiting for some specific event to trigger them, such as an incoming request from a Web browser. Don't confuse daemons with "processes". Processes are "instances" of an application running in memory. For example, the Apache Web server daemon can kick off multiple Apache processes to handle simultaneous requests from multiple browsers. You can see what processes are currently running in your system's memory by typing in the command:

ps -aux

If you installed the Apache Web server software back on the Packages page, you'll see multiple Apache processes running. This number of initial processes is configurable, and if requests from more Web browsers come in than there are processes running, the Apache daemon will kick off more. Other programs will never have more than a single instance (process) running. The number of processes an application will kick off (single or multiple) to handle the load will depend on the design of the application.

Your Home Web Server

We're going to assume you already have a broadband connection and a cable/DSL router which allows multiple computers on your home network to share the connection, and that your Debian system is configured to access the Internet through the router. The cable/DSL router may act as a DHCP server dishing out IP addresses to systems on your home network (Linksys typically dishes out addresses from 192.168.1.101 and higher). However, your Debian server needs to have a static IP address (something like 192.168.1.80).

With a broadband router in place and your Debian system configured with a static address and able to access the Internet through the router, the steps to setting up a home Web server are fairly simple:

- Install and configure Apache (next section).

- Create your HTML and graphics files for your Web pages and FTP them onto your server (they go into the /var/www directory). If you're not a Web developer you can just Google for "free html templates" to get a kick start on creating your HTML pages.

- Set up an account with an organization like EasyDNS to register your domain name and provide DNS resolution services for your domain name (we show you how on the DNS page).

- Configure EasyDNS to use Dynamic DNS for your domain (also on the DNS page).

- Install the ddclient package on your Debian system and configure it to send updates to your EasyDNS account (also on the DNS page).

- Set your cable/DSL router to route all incoming (from the Internet) TCP traffic destined for

port 80 (Web traffic) to your Debian system.

That's it! You're live on the 'Net! Actually, it'll take a few hours for your DNS information (the information ddclient is sending to EasyDNS) to get propogated to the DNS servers of ISPs, but anyone anywhere should be able to browse to your Web server using your domain name by the next day.

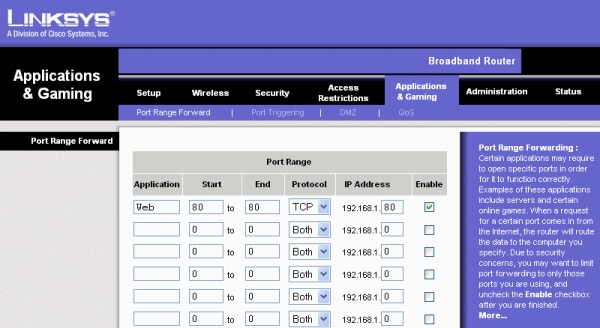

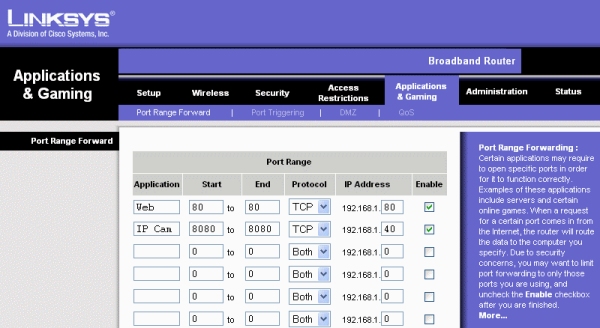

Setting the cable/DSL router to forward all incomingport 80 TCP traffic to your Debian system depends on what type of router you have. On a Linksys router, the port forwarding is found under the "Applications and Gaming" section of the router configuration.

Note that in this example we're assuming your Debian server's static IP address is 192.168.1.80. Be sure to click on the "Save Settings" button at the bottom of this page after entering your port forwarding numbers.

If you are currently using a Web hosting service to host a Web site that doesn't get a lot of traffic, you may want to consider using your home broadband connection to bring your Web site "in house" to save some money. The Easy DNS service is only $35 per year ($55/year if you want to receive e-mail at your domain name) vs whatever you're paying per month for the hosting provider. Not only will you be saving money, but you won't have any disk storage limitations and you can set up your server with CGI or PHP scripts or whatever else you want. Just be sure your site can handle the down-time you'll have when your home cable service or power goes out.

The port forwarding feature of a router can also be used to forward different types of Internet traffic to your server or to different devices. For example, if you were going to set up your Debian server as an e-mail server, you'd want to but in a second entry to forward port 25 (the SMTP port) traffic to your Debian server.

Setting Up An IP Cam

Another example would be to set up an IP camera (also referred to as a network camera) at your home that could be viewed from anywhere on the Internet (or made a part of the Web pages on your Web server). Note that an IP camera is not the same as a typical "Web cam" that connects to a computer. An IP camera is a stand-alone device that contains it's own internal Web server. As such it acts like a stand-alone server.

IP cameras used to costs hundreds of dollars (and the high-end models still do). However, you can now get a low-end IP cam like the

Trendnet TV-IP100 for around $85. Setting up one of these units for Internet viewing is pretty easy.

Because these cameras are self-contained Web servers, they are set to "listen" for requests on port 80 by default. However, port 80 is already being used by our Web server so we need to change that. This is easy to do because we have to go into the Configuration/Network setup menu in the camera in order to change the IP address anyway.

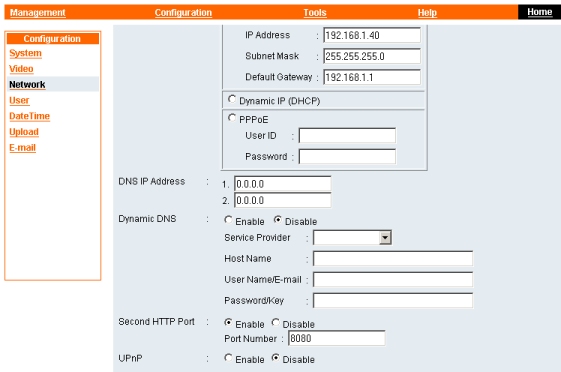

Note that in the above camera configuration page we set the IP address to 192.168.1.40 and set the port the camera should listen on to 8080. (You can use your own values of course.)

Next, we set the cable/DSL router to route port 8080 traffic to the IP camera.

You can browse to your camera from your internal network by using it's IP address and port number as so:

http://192.168.1.40:8080

In order to browse to the camera from the Internet you'll either need to know the external IP address of your router (the IP address assigned to you by your broadband provider) or you'll want to use your own domain name with a dynamic DNS service (see our DNS page for information on how to set that up). If you have this set up already for your Web server, then the URL would be something like:

http://www.you-last-name.net:8080

If you want to set up multiple cameras, you'd just set each camera to use a different port, and put a corresponding entry in the router for each camera.

Setting Up An Apache Web Server

With the release of Lenny Debian no longer supports Apache 1.x. The default version is the newest major version (2.2). From our perspective the main differences between 1.3 and 2.2 are primarily in how configuration files are organized, focusing on virtual hosts.

In Apache-land a virtual host equates to a Web site. Virtual hosts are what allows a single Apache Web server to serve up multiple Web sites which is why there are so many Web hosting companies out there. You set up one Linux (free software) server and install Apache (free software) on it and you can host hundreds of Web sites, charging each Web site owner a monthly fee to have their site on the server. If you go through the trouble of setting up a home Web server to host your Web site(s), there's not a lot of work involved in also hosting sites for your friends and family members.

All we need to do to install Apache is enter the command:

apt-get install apache2

The will install the Apache application and all dependent files. After the installation Apache starts automatically and is set to start automatically when the system is booted

If you just want to play around with a Web server and not have a domain name associated with it (like with a test Web server) you're pretty much done. You can verify Apache is working by going to another system on the same network as your Debian server and entering the address of your Debian server in the browser's address line, something like:

http://192.168.1.80

A page should appear with the words "It works!" at the top of the page. This is the default /var/www/index.html file that comes with the apache2 package. You can add your own pages into the /var/www directory.

You may have noticed that the open-ssl package also got intalled. This will allow you to play around with a Web server that has support for SSL (Secure Sockets Layer) for accepting secure transactions. However, since the servers we set up on these pages are not very secure, you wouldn't want to use this SSL server in a production environment. SSL will let you encrypt information that is submitted to the Web server, but if the underlying OS is not secure that sensitivie information can be stolen off the disk. You'd also need to get a certificate from an outfit like Thawte or Verisign in order to use the SSL capabilities of the Web server. (They offer temporary certificates for free that you can use if you want to play around with SSL.)

The main configuration file for Apache is the /etc/apache2/apache2.conf file. Like just about every Linux/UNIX configuration file, it is a plain old ASCII text file so you just use a text editor to make changes to it. Luckily, the defaults in the configuration file are pretty much what we need.

The way Debian's Apache 2.2 package sets things up makes it easy to add (and remove) Web sites (virtual hosts) to your server. The two directories you need to focus on are /etc/apache2/sites-available and /etc/apache2/sites-enabled and these two directories are specific to Debian (and Debian derivatives such as Ubuntu). Actually, the /etc/apache2/sites-enabled directory just contains sym links to the files in the /etc/apache2/sites-available directory. That's how you enable and disable sites, just add and remove sym links in the "-enabled" directory. (Sym links are like shortcuts in Windows.)

There's already a file called default in the /etc/apache2/sites-available directory. And there's already a sym link to it in the /etc/apache2/sites-enabled directory called 000-default which is a special name. The link name ensures it is read first at startup by Apache even when other sym links (for additional Web sites) are added to the directory.

A Single Web Site

If you want to set up a real Web server that hosts one Web site (one domain name) then you don't have to do much. That's because that only the one domain name will have a 'www' DNS record which points to this server. You may want to edit the default configuration file with the command:

nano /etc/apache2/sites-available/default

and enter your e-mail address in place of 'webmaster@localhost' on the line:

ServerAdmin webmaster@localhost

You may also want to add a line just beneath it with your domain name so it has something to use for the server signature. (However, as you'll see below, you may want to disable the server signature function.) Add the line something like:

ServerName www.your-last-name.net

Then press Ctrl-X to exit the editor and save the file. Now you can just load your HTML files and images into the /var/www directory.

Multiple Web Sites

If you want to host multiple Web sites on your server (i.e. use the Virtual Hosts feature of Apache) you'll need to set things up a little differently. In the following examples we're going to set up the following three Web sites: moe.com, larry.com, and curly.com. Because the 'www' DNS records for each of these domains are all going to point to the same IP address (and all use the same port 80) we'll be using Apache's name-based virtual hosts. With name-based virtual hosts, the browser includes the domain name in the HTTP request it sends to the IP address of the Web server. This is how Apache knows which Web site is being requested. Very early browsers didn't support name-based virtual hosts but all current browsers do.

The first thing you need to do is create a "document root" sub-directory for each Web site under the /var/www directory. In our example you would enter the following commands to do this:

mkdir /var/www/moe

mkdir /var/www/larry

mkdir /var/www/curly

Note that the sub-directory names don't have to match the domain names. It just makes it easier to follow if they are.

You also have to do the same for the CGI sub-directories.

mkdir /usr/lib/cgi-bin/moe

mkdir /usr/lib/cgi-bin/larry

mkdir /usr/lib/cgi-bin/curly

Each Web site needs it's own file in the /etc/apache2/sites-available directory and, to be enabled, it's own sym link in the /etc/apache2/sites-enabled directory. In each file you enter that site's "virtual host block."

Since we want to keep the '000-default' sym link and the 'default' file it links to, we'll recreate the 'default' file. So that we can go back to a clean slate later if we need to, we'll save original file by renaming it with the command:

mv /etc/apache2/sites-available/default /etc/apache2/sites-available/_default

Then create a new 'default' file with the command:

nano /etc/apache2/sites-available/default

and enter the following statements into it:

<VirtualHost *:80> ServerAdmin stooge@moe.com ServerName www.moe.com ServerAlias moe.com DocumentRoot /var/www/moe/ # Set Document Root directory options <Directory /> Options FollowSymLinks -Indexes Includes # Allow use of .htaccess file AllowOverride Limit FileInfo </Directory> ScriptAlias /cgi-bin/ /usr/lib/cgi-bin/moe/ # Set CGI-BIN directory options <Directory /cgi-bin> AllowOverride None Options +ExecCGI -Multiviews +SymLinksIfOwnerMatch Order allow,deny Allow from all </Directory> CustomLog /var/log/apache2/moe-access.log common ErrorLog /var/log/apache2/moe-error.log </VirtualHost>

Press Ctrl-X to exit the editor saving the file. Create a copy of this file for our second site with the commands:

cd /etc/apache2/sites-available

cp default larry

Then open the newly-created file in a text editor with the command:

nano larry

and make the relevant changes:

<VirtualHost *:80> ServerAdmin developer@larry.com ServerName www.larry.com ServerAlias larry.com DocumentRoot /var/www/larry/ # Set Document Root directory options <Directory /> Options FollowSymLinks -Indexes Includes # Allow use of .htaccess file AllowOverride Limit FileInfo </Directory> ScriptAlias /cgi-bin/ /usr/lib/cgi-bin/larry/ # Set CGI-BIN directory options <Directory /cgi-bin> AllowOverride None Options +ExecCGI -Multiviews +SymLinksIfOwnerMatch Order allow,deny Allow from all </Directory> CustomLog /var/log/apache2/larry-access.log common ErrorLog /var/log/apache2/larry-error.log </VirtualHost>

Press Ctrl-X to exit the editor saving the file. Then create another copy of the original file for our third site with the command:

cp default curly

Then open the newly-created file in a text editor with the command:

nano curly

and make the relevant changes:

<VirtualHost *:80> ServerAdmin webmaster@curly.com ServerName www.curly.com ServerAlias curly.com DocumentRoot /var/www/curly/ # Set Document Root directory options <Directory /> Options FollowSymLinks -Indexes Includes # Allow use of .htaccess file AllowOverride Limit FileInfo </Directory> ScriptAlias /cgi-bin/ /usr/lib/cgi-bin/curly/ # Set CGI-BIN directory options <Directory /cgi-bin> AllowOverride None Options +ExecCGI -Multiviews +SymLinksIfOwnerMatch Order allow,deny Allow from all </Directory> CustomLog /var/log/apache2/curly-access.log common ErrorLog /var/log/apache2/curly-error.log </VirtualHost>

Press Ctrl-X to exit the editor saving the file.

Now that we have the necessary files in the /etc/apache2/sites-available directory we need to create the sym links to them in the /etc/apache2/sites-enabled directory. Because moe.com was set up in the 'default' file it's already got a link so we only have to do the other two. Debian has a utility that makes this easy for us. Enter the following commands to enable the other two sites:

a2ensite larry

a2ensite curly

Now restart Apache so it reads our new configuration with the command:

/etc/init.d/apache2 reload

Your Web server is all set up but your name resolution isn't. If you want to test your server you'll need to modify the hosts file on your PC entering the IP address of your server for each of the domains like so:

192.168.1.80 www.moe.com

192.168.1.80 www.larry.com

192.168.1.80 www.curly.com

Assuming you've changed the port forwarding in your cable/DSL router to forward port 80 traffic to your Web server, in order for people on the Internet to access your Web server you'll need to update the DNS records for the domains. We cover this on the DNS page. (Be sure to remove the above entries from your hosts file once you've got the DNS updated.) Note that in our example above you'd need to register each of these domain names and get DNS services for them. If you get all your domain names from a provider like EasyDNS you can update the dynamic DNS information for all of them simultaneously. We show you how to update multiple domains simultaneously on our DNS page.

SSI - Server Side Includes

SSI is just what the name implies. When Apache is serving up a Web page (HTML file) it can look through ("parse" the HTML code looking for SSI statements (called 'directives') embedded in the HTML code of Web pages. These directives retreive certain information, such as date or time or even the contents of other files and Apache includes this information in the page it sends to the browser. For instance, a common usage of SSI is to have one header or footer file for all Web pages and have them included in every page. That way if you need to change the HTML in the header or footer you don't have to change every page, just the one or two files that get included. Some CGI scripts can only be run via an SSI directive. Apache finds the SSI directive instructing it to run the script, runs the script, and then takes the output of the script and includes it in the Web page where the directive is located. Apache won't look through ('parse') HTML pages looking for SSI directives by default. We have to do two things to enable it:The Debian implementation of Apache handles modules like it handles sites. There's a /etc/apache2/mods-available directory that has 'load' statements for a lot of modules and a /etc/apache2/mods-enabled directory that you create sym links in to enable modules. To have Apache load the includes module we enter the following commands:1. Add the Includes option to the configuration file (we did this above)

2. Have Apache load the includes module when it starts (we'll do this below)

3. Give HTML files a .shtml extension

cd /etc/apache2/mods-enabled

ln -s ../mods-available/include.load

Now we have to restart Apache with the command:

/etc/init.d/apache2 reload

That's all there is to it! You're now ready to start serving up SSI-enabled Web pages.

If you want to test the SSI functionality use the text editor to create this simple Web page:

nano /var/www/test.shtml

and enter the following HTML code into it:

Note that the only content of our Web page is an SSI directive to get the system environment information. Exit the editor saving the file. Now go to a different system on the network, fire up a Web browser, and enter the URL using the server's IP address like so:

http://192.168.1.80/test.shtml

If your Debian system isn't on a network or you don't have access to another machine but you still want to see if it works, you have a couple options. You can fire up the GUI and Mozilla on the server machine itself and enter the following URL in the browser:

http://127.0.0.1/test.shtml

Securing Apache

There are numerous ways to harden an Apache installation. If your firewall is properly configured the only traffic that should get to your Web server would be traffic going to port 80 (i.e. HTTP traffic). However, HTTP traffic can still be malicious.

Many of Apache's error pages have a footer with a horizontal line and the text:

Apache/2.2.9 (Debian) Server at www.moe.com Port 80

Often times hackers will send bogus HTTP requests to get the server to generate these error pages because the information about the server OS and Apache version can be useful to them. We can reduce the information given out in such instances by making a couple simple changes to a security file. Open the file in a text editor with the command:

nano /etc/apache2/conf.d/security

Look for the lines:

# ServerTokens Minimal

ServerTokens Full

....

# ServerSignature Off

ServerSignature On

and reverse the comment character on these two pairs of commands so they read:

ServerTokens Minimal

# ServerTokens Full

....

ServerSignature Off

# ServerSignature On

Exit the editor saving the file and restart Apache.

Any file put in the /etc/apache2/conf.d directory will be read by Apache when it starts.

While the above changes will cut down on the information given out about our server it won't do anything for malicious HTTP requests. Luckily there's an Apache module called mod_security that acts like an IDS (Intrusion Detection System) monitoring incoming HTTP requests and denying access to any requests that look suspicious. For instructions on how to set up mod_security see the "Securing Apache" section of our Security page.

The important file locations for Apache on a Debian system are:

Configuration files directory (aka "ServerRoot") - /etc/apache2 - Web page files directory (aka "DocumentRoot") - /var/www

- CGI scripts directory (aka "cgi-bin") - /usr/lib/cgi-bin

- Log files directory - /var/log/apache2

- The Apache executable file - /usr/sbin

You can tell which version of Apache you're running using the command:

/usr/sbin/apache2 -v

Where to learn more - The best of our bookshelves:

More info...Trust me, Linux Apache Web Server Administration is the only Apache book you'll need. It thoroughly covers Apache and all the goodies including both IP-based and name-based virtual hosting, advanced directives, CGI, SSI, SSL, redirection, and using modules. If you want to set up a Web server that requires someone to log in to view the site's contents there's an entire chapter on options for how to do this. He also gives some sample Web pages (the HTML code for them) that you can use to securely monitor your Apache server over the Web and test out SSI. It's written in a manner that's easy for Apache newbies to understand while not boring those with some experience with it. The file locations given in the book are for a vanilla Apache installation and most Linux distributions tend to rearrange things a bit. However, that's an easy adjustment to make. (See our list of file locations above.)

Testing Apache

You can use telnet to act like a browser to test out Apache. You can use any computer on the same local network to run telnet and connect to port 80 (that's the port HTTP listens on) on the server to issue the commands. Assuming your Debian system's IP address is 192.168.1.10 the following command will connect you to the HTTP service. On a Windows system, click on the Start button and select Run and enter the command in the input field.

telnet 192.168.1.40 80

If you don't have another system to try this from you can get on the Debian system and enter the above command using localhost in place of the IP address. Once you're connected (you won't see anything appear on the screen upon connection), type in the following command being sure to use the upper-case syntax as shown (the characters will not echo when you type them):

GET / HTTP/1.0

and press Enter twice. You should see the HTML code of the home page go flying by. The first slash in the command is the page specification. When no page is specified the home page (i.e. index.htm) is returned. To specify a page, enter the page name after the slash (i.e. /test.shtml).

Above the page's HTML code is the HTTP "header" which looks something like this:HTTP/1.1 200 OKYou can also see this information by entering this command while still telneted into port 80 of the server:

Date: Wed, 25 Feb 2009 22:18:37 GMT

Server: Apache/2.2.9 (Debian)

Connection: close

Content-Type: text/html;

HEAD / HTTP/1.0

(Be sure to press Enter twice after entering it.) Why would you want to do this? For troubleshooting and testing mainly. Some times you'll try and pull up a Web page and get nothing but a blank white background. The above GET command will show you what, if anything, the Web server is sending the browser.

You can also see the output generated by certain CGI scripts (scripts that generate output intended to be displayed on Web pages) that you may have installed. Simply specify the path and name of the script in the GET command:

GET /cgi-bin/hitcount.cgi HTTP/1.0

Another reason is automation. Do you check certain Web pages on a daily basis (or would if you had time)? Once you get good at script writing you could probably write a script that would retreive a page, parse it for desired information and extract it when it finds it, and then e-mail just that information to you.

Secure Web servers, the type that use SSL for https-type connections (the type that give the closed-lock symbol on your browser's status bar), are not for the casual server administrator. Having a secure Web server not only involves having the SSL software added to your Apache installation as we mentioned near the top of this page, but requires that the operating system be hardened to prevent unauthorized access. Then there's the issue of obtaining an SSL "certificate" from an outfit like Verisign and installing that on the server (and they have to be renewed annually for a fee). If you're collecting or serving data that requires a secure connection, chances are the sources of that data would sue you if it ever got into the wrong hands. These types of secure servers are best left to professional hosting companies, whether they be for e-commerce or other functions. That's not to say you should never try and set up an SSL Web server. Just be prepared to do a considerable amount of studying and work. You'll need to be knowledgable not only in the areas of SSL software for Apache and server certificates, but quite a student in the area of overall Linux OS security as well.

Light the LAMP

It's so common these days to use PHP and MySQL with Apache that such servers are referred to simply as LAMP servers (Linux, Apache, MySQL, PHP). Whereas installing Apache alone allows you to serve up static "brochure" type Web pages, CGI, PHP, and MySQL can turn you Web server into an Internet application server.

Adding PHP support to your Web server may be a good idea even if you don't plan on using MySQL. Like Perl CGI sripts, there are a ton of freely downloadable PHP scripts available on the Web. (Whereas Perl scripts are contained in their own separate file, PHP scripts are contained in Web (html) pages which are given a .php extension.)

NOTE: There is a downside to installing PHP on your Web server. I can tell you from personal experience that hacking attempts against your Web server will increase dramatically once you install PHP because hackers will probe for insecure legacy files and scripts. Unless you need the functionality provided by a PHP script, err on the side of security and don't install PHP.There's a lot you can do with PHP that doesn't have anything to do with databases. However, if you want to use your PHP pages to access MySQL databases, you'll have to install MySQL and a libraries package. To install the MySQL package, enter:

apt-get install mysql-server

Select Yes to start MySQL at boot up and take note of the information given on the Install Hints screen.

Now we install the library files with the command:

apt-get install php4-mysql

That's it! All we have to do is restart Apache so the PHP module gets loaded with the command:

/etc/init.d/apache restart

You can verify that Apache is now supporting PHP by creating an HTML file with the command:

nano /var/www/test.php

and add the following lines to it:

<html>

<body>

<?php phpinfo(); ?>

</BODY>

</HTML>

Exit the editor saving the file and get on a system that's on the same network as your Debian system and fire up the Web browser and see if you can pull up the PHP page. If your Debian system has an IP address of 192.168.0.10 then you'd enter the following URL in your browser:

http://192.168.0.10/test.php

If your Debian system isn't on a network you can start up the GUI, fire up the Mozilla browser, and replace the address in the above URL with 127.0.0.1 (the local system's loopback address). While the above HTML code doesn't look like much, you'll get a LONG page with all kinds of system and environment information. Most of this is a result of the phpinfo() function embedded in the HTML.

As with any programming language, scripting languages included, it's always good to have a test server to test out new pages and code development. One error in the code can crash a server or cause an endless loop bringing a server to its knees. As you can see, setting up a test PHP server is easy so there's no reason to risk bringing down a production Web server if you plan to do any PHP development.

When using PHP pages to access a MySQL (or any other) database, you can have the Web server hosting the PHP pages be on a separate system from the database server running MySQL. This is most often the case if your database is accessed by both external visitors to your Web site and internal company employees. In this instance, you can put the Web server inside the DMZ and the database server on the internal LAN. Then you'd just set up the appropriate rules on the inside firewall to allow traffic between the two systems. (We cover this on the Firewalls page.) However, there's no reason why both PHP and MySQL can't be set up on the same system if they'll be accessed exclusively by either internal employees (locate it on the LAN) or external Web visitors (locate it in the DMZ). One exception to this may be if the data you collect on via a Web site and store in the database is of a sensitive or private nature. In this case, the data would be more secure if it was stored on a separate database server that's not located in the DMZ.

On the Database Server page we'll show you how to use MySQL to create a database and try a test to make sure the Debian system is indeed acting as a database server.

Setting Up A Sendmail E-mail Server

Debian installs the Exim mail server software by default when you do even a basic installation. Sendmail is much more widely used and much more powerful. It's sendmail.cf configuration file is legendary in it's complexity. But due to its complexity, if you ever need any special configuration features, there's likely a way to set up exactly what you want.

Also included with Debian is a package called MailScanner that you can use on your e-mail server to scan incoming attachments for viruses. A link to the MailScanner Web site is given on the Resources page.

There's actually two server services involved with a mail server. First, you have an MTA (Mail Transport Agent) that is responsible for exchanging mail with other mail servers and forwarding mail that is being sent by clients. This is the part that Sendmail handles (i.e. Sendmail is an MTA).

Then there's the service which allows POP clients to log in and retrieve their mail from the server. The mail messages are transferred from the user's "mailbox" (a file) on the server to their "inbox" (a file) on the user's local hard-drive. Sendmail doesn't do POP so we need to install that separately.

The MTA service uses the SMTP (Simple Mail Transfer Protocol) protocol to transfer and forward mail. The POP service uses the POP3 (Post Office Protocol v3) to send messages from the server to the client. You'll see examples of both of these protocols in action later in this page.Terminology:If you didn't edit the /etc/resolv.conf file back on the Modem page, you'll want to

- MTA - Mail Transport Agent The server-based application that routes mail from MUAs (clients) to other MTAs and accepts mail from other MTAs. Sendmail is the most popular MTA. Exim and Microsoft Exchange are others. MTAs use the SMTP protocol to accept and route mail from MUAs and to send/receive messages to/from other MTAs.

- MUA - Mail User Agent This is the nerd term for the e-mail reader client software run on most PCs. Common MUAs are pine and elm (UNIX/Linux), Netscape Communicator, Eudora, and Microsoft Outlook (Windows). They use the SMTP protocol to send messages and the POP protocol to retreive messages.

- SMTP - Simple Mail Transport Protocol "Protocol" is just a fancy term for "a set of rules that you have to follow". With SMTP (and many other communications protocols) the "rules" are the commands and their syntax (which you will see in action below). The SMTP protocol is a set of commands used to communicate with/between MTAs. SMTP listens on port 25.

- POP - Post Office Protocol A message retrieval protocol (commands) used to communicate with a POP service running on a mail server. The most commonly-used versions are POP2 and POP3. popd is one of the most common POP daemons run on mail servers. An MUA uses POP commands to communicate with the POP service (daemon) to retreive any messages stored in a mailbox file. IMAP (Internet Message Access Protocol) is another common message retrieval protocol. POP listens on port 110.

go back there and enter your ISP's DNS server settings (or whatever DNS server settings your network uses).

It doesn't matter if you don't have a real domain name. If you just want to try this for fun you can send out Internet e-mail from the non-existant domain name you may have entered when you installed Debian (recall we recommended using your-last-name.net as your domain name). Even with this non-existant domain name however, your mail server won't be using your ISP's mail server for anything. It will be a stand-alone mail server sitting on the Internet able to directly send e-mails. In order to receive e-mails we'd need to set up DNS which we cover on theDNS Services page.

In the real world, Sendmail can act as a mail server for your internal or home network only, or it can handle your internal mail and your external (Internet) mail provided you have a valid domain name. You can even send messages to different users on the same machine. For example, during the installation you created a user account. While logged in as root, you could send an e-mail to this user and the view it the next time you log in as that user. To do this you enter only the user name in the "To:" field.

In the case of a real mail server, it is tempting to connect your mail server to the Internet and your local LAN so that users can retrieve their mail messages directly from the server over a LAN segment. However, whenever you connect a server to an internal network and the Internet it's a security risk, acting as a bridge between the two networks.

You're better off only connecting the systems to the Internet and letting your users retreive their mail from the server over your Internet connection. The most efficient way of doing this is to set up pop clients (mail readers) on the users workstations to access the mail server using the IP address of the server's interface connected to the Internet. By using the IP address no DNS queries need to be made. If there will be a firewall between your mail server and your internal network you have to be sure to allow POP and SMTP traffic (ports 110 inbound and 25 outbound respectively) through the firewall.

The first thing you have to do is install the Sendmail package. (When you install Sendmail, apt will remove Exim.) To install it you simply enter the command:

apt-get install sendmail-bin

and you'll will be prompted to insert the Debian CD #1. During the installation you'll see some error messages because we never configured Exim. These can be ignored.

Sendmail advises against editing the sendmail.cf configuration file directly. Configuration is typically done using a utility called the "m4 processor". You place easier (somewhat) to understand statements in the sendmail.mc configuration file which m4 uses as input. Based on the statements in the sendmail.mc file m4 spits out the corresponding sendmail.cf configuration file which is read directly by Sendmail when it starts up.

Debian has it's own Sendmail setup utility (which uses m4) to configure Sendmail. Before we run it we need to make some changes to the sendmail.cf configuration file. At the shell prompt type in

cd /etc/mail

to switch to the directory where the Sendmail configuration files are stored. While in the /etc/mail directory open the sendmail.mc file with the nano text editor by typing in:

nano sendmail.mc

Comment out the following three lines by putting dnl in front of them so they look like this:

dnl FEATURE(`no_default_msa')dnl

dnl DAEMON_OPTIONS(`Family=inet, Name=MTA-v4, Port=smtp, Addr=127.0.0.1')dnl

dnl DAEMON_OPTIONS(`Family=inet, Name=MSP-v4, Port=submission, Addr=127.0.0.1')dnl

Arrow down the end of the last line in the file and press Enter to create a blank line and enter the lines below.

Note that while local and smtp is enclosed in single quotes, note that they are NOT the same quote character. The first (opening) quote is the key that's in the upper-left corner of most keyboards while the second (closing) quote is the key that's next to the Enter key on most keyboards.

MAILER(`local')dnl

MAILER(`smtp')dnl

Cw debian.your-last-name.net

Cw your-last-name.net

Replace the above FQDN and domain name with your values. Then exit the editor saving the file. Now configure Sendmail by typing in the following at the shell prompt:

sendmailconfig

and pressing Enter. You'll be asked a series of questions. Answer them as follows:

- Accept the default Yes to the prompt about using the sendmail.conf file by pressing Enter

- Accept the default Yes to the prompt about using the sendmail.mc file by pressing Enter

- Accept the default Yes to the prompt about restarting Sendmail with the new configuration by pressing Enter

That takes care of Sendmail. Note that you can change your Sendmail configuration any time by changing the values in the /etc/mail/sendmail.mc file and re-running the sendmailconfig utility.

Now you'll also want to edit the /etc/hosts file.

nano /etc/hosts

and make sure the line for the local system contains the following:

- the IP address of your system followed by a Tab character

- the host name of your system followed by a Tab character

- the FQDN (Fully Qualified Domain Name) of your system followed by a Tab character

- the words loghost and mailhost separated by a space

When you make the changes the top of the file should look like this:

127.0.0.1 localhost.localdomain localhost 192.168.10.10 debian.your-last-name.net debian loghost mailhost

Exit the editor saving the file. That's it! Your e-mail server is set up.

At this point you have to restart Sendmail because it only reads the configuration file when it starts. However, given the file edits we've made it may be wiser to just reboot the system.

If you read through ourDNS Services page and you're using a DNS service like EasyDNS.comyou'll want to update your MX (Mail eXchange) DNS record to point to your server. (You may need to rerun the ddclient program as detailed on the

DNS Services page after doing so.)

In the case of a real mail server you'd have to tell your ISP (or whoever is hosting your DNS records) to change the MX record for your domain so that it points to the IP address of the Internet-connected interface of the mail system (or of the firewall that's doing a static address translation to the mail system).

The important file locations for Sendmail on a Debian system are:

- Configuration files directory - /etc/mail

- Incoming mail queue directory - /var/spool/mail

Messages are stored in files with names that match each username. These are the user "mailbox" files that are kept on the server. Each mailbox is a single file that can contain multiple messages. This file is usually cleared out when a user's POP client downloads their messages to their inbox (unless the POP client is set to "leave messages on server").

- Outgoing mail queue directory - /var/spool/mqueue

With a full time Internet connection this directory should be empty because the messages will get sent out as soon as the recipient's domain name is resolved via DNS (i.e. almost immediately).

- The Sendmail executable file - /usr/sbin

To find out what version of Sendmail you're running, as well as some other information which will allow you to verify your Sendmail configuration, use the command:

/usr/sbin/sendmail -d0.4 -bv root

The version number is the first line to be displayed so if so much information is displayed that it scrolls off the top of the screen you can either pipe (i.e. append| more to the end of the above command) or press Shift-PgUp to scroll the display up.

Where to learn more - The best of our bookshelves:

More info...O'Reilly's book Sendmail, commonly referred to is "the bat book", is the industry bible when it comes to Sendmail. However, it's definitely not the first book on Sendmail you want to read. Linux Sendmail Administration is the companion to the above Apache book and is just as well written (enjoyable for both Sendmail newbies and those with some experience) and just as wide in it's coverage of the application. In addition to installation and configuration (both m4 and manual), chapters address implementing anti-spam measures and application security. It also covers all of the technical goodies of Sendmail such as uing databases and rewrite rules. However, this isn't until after the first two chapters show how Internet e-mail works and present a high-level overview of the functional parts of Sendmail. Having wrestled with Sendmail a few times in the past I can tell you that a book like this was sorely needed.

Note that the Sendmail people only support using the 'm4' processor to configure Sendmail (not the sendmailconfig utility provided by Debian). The usage of of m4 is covered in the above book.

The POP Server

Now we have to set up the POP server. There's a basic POP server included in the Debian packages called ipopd. To install it (you should know this by now) put the Debian CD #1 in the drive and type in:

apt-get install ipopd

Answer Yes to allowing insecure authentication and answer Yes again to installing libc-client without Maildir support.

On the configuration screen arrow down to 'pop3s' and press the Space Bar to de-select it. Then Tab to OK an press Enter.

If you want to test it, just get on a different system on your local network, fire up the e-mail client, and change the POP server settings to point to the IP address of your Debian box. You'll need to change the user name and password in the client to match the user account you created during the Debian OS install. A POP server will automatically see any user on the Debian system as an e-mail user and it will use the Debian user name and password.

Note that you typically can't enter more than one POP server in an e-mail client (like you can with IMAP servers). Because of this you'll have to delete your current POP server settings (likely the settings for your ISP) before you can enter your Debian system settings. If you don't know them by heart, be sure to write down the POP server name, user ID, and password of your current POP server settings before you delete them.

Testing Sendmail (SMTP)

You can use very basic mail program to try and send an e-mail. It gets installed by default when you install Debian.

Note: If you're using a fictitious domain name on your Debian mail server, don't send mail messages to those who receive their e-mail via an ISP. Many ISPs will resolve the domain of incoming mail to cut down on spam. You'll want to send it to someone at a school district, university, local government agency, or a mid-size company. These types of organizations may have their own mail server and typically don't do DNS resolving of incoming mail.To send an e-mail using the mail program:

- If necessary, use the pon command to connect to your ISP.

- At the shell prompt type in the word mail followed by the e-mail address of the recipient

(ex: mail junior@college.edu ) and press Enter.

- The Subject: line will appear so just enter an appropriate subject and press Enter.

- Type in the text of your message. You can hit Enter to insert line-feeds in your message if you want. Ask the recipient of the message to forward this message onto your regular e-mail address so you can take a look at it. If you're using a fictitious domain name you may also want to add a note telling them not to reply to the message. If they did, their reply would just get bounced back to them because their mail server would be unable to resolve your ficticious domain name.

- When you're done typing your message hit Enter to put the cursor at the beginning of a blank line and press the Ctrl-D key sequence.

- The Cc: line will appear where you can enter another address if you want.

- At this point, if you are connected to the Internet via an external modem, you may want to keep an eye on the Tx/Rx indicators. After you've entered a cc: address, or chose not to enter one, press the Enter key to send the mail. With the external modem you should see the indicators flash as your ISP's DNS server is contacted to resolve the recipient's domain name and the mail is sent.

After a minute or so type in mail on the command-line by itself (i.e. no e-mail address after it) it will check to see if you have any mail waiting for you. If your mail was rejected by the receiving SMTP server there should be an e-mail containing an error message as to why.

Troubleshooting

Because of Sendmail's complexity there are a myriad of error messages you could see in mail that gets returned to you. The sendmail.org Web site has extensive FAQs which list most of these errors and what to do about them.

If you run into a situation where your network clients are having problems sending e-mail you can pretend to be an e-mail client sending an e-mail by using telnet to issue SMTP commands to the server. You can use any computer on the same local network to run telnet and connect to port 25 (that's the port SMTP listens on) on the server to issue the commands. Assuming your Debian system's IP address is 192.168.1.10 the following command will connect you to the SMTP service. On a Windows system, click on the Start button and select Run and enter the command in the input field.

telnet 192.168.1.10 25

If you don't have another system to try this from you can get on the Debian system and enter the above command using localhost in place of the IP address. However, running telnet on the local server system won't tell you if you have a network connection problem with the e-mail server.

In the following example, the lines in bold are the commands you enter to pretend you're a mail client sending an e-mail message through the server. The lines in italics are the responses you should see from your server. Make sure that the mail server can "see" a DNS server, whether it be over an Internet connection to your ISP's DNS servers or your own local DNS server. (Use pon to dial into your ISP if necessary.) You'll be able to tell if your Debian server can't see a DNS server. It's responses to the commands you enter below will be VERY slow in coming. After you connect via telnet the server will respond and wait for your commands.

The your-id is the username of the user account your created during the Debian installation.

(telnet connection established) 220 debian.your-last-name.net ESMTP Sendmail 8.13.1/8.13.1/Debian-17; Fri, 26 Nov 2004 20:34:10 -0600 (CDT) (No UCE/UBE access) helo your-last-name.net 250 debian.your-last-name.net Hello solarisi [192.168.10.30], pleased to meet you mail from: your-id@your-last-name.net 250 2.1.0 your-id@your-last-name.net... Sender OK rcpt to: root@your-last-name.net 250 2.1.5 root@your-last-name.net... Recipient OK data 354 Enter mail, end with "." on a line by itself This is a test mail message sent to root . 250 2.0.0 Message accepted for delivery quit 220 2.0.0 debian@your-last-name.net closing connection

In the above example we were sending mail from a non-root user to the root user in the same domain (but using different systems). If you tried to use arcpt to: address that was not in the same domain you'd likely get a relaying denied error.

The most common SMTP return codes are as follows:

220 - Service ready

221 - Service closing transmission channel

250 - Requested mail action okay, completed

354 - Start mail input; end with <CRLF>.<CRLF>

421 - Service not available, closing transmission channel

450 - Requested mail action not taken: mailbox unavailable

500 - Command unrecognized (mis-spelled command or wrong syntax)

501 - Syntax error in parameters or arguments

502 - Command not implemented (valid SMTP command but not available)

550 - Requested action not taken: mailbox unavailable

551 - User not local; please try <forward-path>

554 - Transaction failed

POP Too

You can also use telnet to pretend to be a POP client as well. This time you connect to port 110 which is the port POP listens on. Again, using 192.168.1.10 as an example address for the server, enter the following command:

telnet 192.168.1.10 110

As above, you can also use the following command on the local system:

telnet localhost 110

In the following example, the lines in bold are the commands you enter to pretend you're a mail client checking for e-mail messages. The lines in italics are the responses you should see from your server. After you connect via telnet the server will respond and wait for your commands.

Note that you CANNOT try this using the root mail account because the password is sent in clear text. Use the name of the user account you created during the Debian installation.

(telnet connection established) +OK POP3 debian.your-last-name.net v2003.03 server ready user keith +OK User name accepted, password please pass penguin +OK Mailbox open, 1 message list +OK Mailbox scan listing follows 1 2050 2 4213 3 928 . retr 1 +OK 2050 octets (header and message text gets typed to the screen) . dele 1 +OK deleted quit +OK closing connection

The dele dialog in blue is optional. You don't need to enter the dele command if you want to keep the message in your mailbox file on the server. It normally is used because POP clients transfer the mail from the mailbox on the server to an "inbox" on the client's hard-drive. In most POP client software (Netscape Communicator, Eudora, Outlook) you'll see an option to "leave messages on server". If this option is selected, the dele command isn't executed.

Internet Services and TCP Wrappers

If you set up your system according to the Installation and Packages pages on this site, you probably noticed that when you boot the system you see the following right above the the login prompt:

Starting mail transport agent: sendmail.That's no big surprise because we installed those packages. However, we also installed the ipopd and wu-ftpd server software packages. Where are they? They are handled a little differently.

Starting web server: apache.

If you look above the login prompt you'll also see the line:

Starting internet superserver: inetd.inetd is the daemon that idles in the background listening to the ports that certain Internet-based service requests (POP, telnet, FTP, etc.) come in on. When it detects a request on a specific port, it calls the appropriate process (server software program) to handle the request. This is also why you won't see POP or telnet or FTP listed if you issue the command:

ps -aux

to list all of the processes running on the server. You will however see the inetd process (daemon) running.

You control which ports inetd listens on by editing the /etc/inetd.conf file. A typical line in this file could look like this:

ftp stream tcp nowait root /usr/sbin/wu-ftpd

This line was added to the file when you installed the wu-ftpd package above. It is simply telling the inetd daemon to run the /usr/sbin/wu-ftpd program when a request comes in on the FTP port (Port 21). Note that I said the line could look like this. It likely doesn't. It probably looks like this:

ftp stream tcp nowait root /usr/sbin/tcpd /usr/sbin/wu-ftpd

Note the additional part in blue. This tells the inetd daemon to run the tcpd program when a request comes in on the FTP port. The /usr/sbin/wu-ftpd path to the ftp daemon is used as a command line parameter to the tcpd program. The tcpd program is run first and it "calls" the wu-ftpd program.

What is tcpd? It's called a TCP "wrapper" because it runs the actual program within itself. It wraps itself around the execution of the actual program so it can watch the traffic that goes in and out of the program. It's a security tool.

When you use the tcpd wrapper program you can control it using the /etc/hosts.allow and /etc/hosts.deny files. Just as the file names imply, the TCP wrapper allows you to control who can access these services.

For example, you can allow only a specific computer to telnet into your server by specifying that computer's IP address in the /etc/hosts.allow file. If you enter only the first two or three octets of an IP address, only the machines that have addresses that start with those octets will have access.

The format of the statements in the two hosts files, and how the two files interact, are beyond the scope of this page. We just wanted to make you aware of what TCP wrappers are because you'll often see it mentioned in Web documents. It's a very useful and valuable security tool and it would be well worth your time to learn how to use it.

For example, you could set up a server at work to only allow telnet from systems on your home ISP's subnet so you can get at it from home. Yes, others on your ISP's subnet would also be able to telnet in if they were able to crack a username and password, but this is a lot more restrictive than the entire Internet. The reason you'd have to use your ISP's subnet is because your home computer is assigned a dynamic (changing) address each time you connect to your ISP so you wouldn't be able to use a specific IP address in the /etc/hosts.allow file.

In addition to controlling access through the use of the two hosts files, TCP wrappers also help to prevent spoofing attacks. Note that the 2.4 Linux kernel uses a program called xinetd in place of inetd. Setting your system up to use SSH (Secure SHell) access instead of telnet is also another good security measure as login information (username and password) are sent as clear text when using telnet. The unsername and password are encrypted with SSH. (See the Resources page for a link to a nice SSH client for Windows that is free for personal use.)

There are other ways to help secure a server also. As mentioned on the Basics page, you can customize runlevel 2 so that services like NFS and lpd don't start when you boot the server. This is done by renaming their symbolic links in the /etc/rc2.d subdirectory so their names don't start with an upper-case S.

SECURITY WARNING

Do NOT plan to use the system you will create using these guide pages as a "production" (real) server. It will NOT be secure!

There are many steps involved in creating a secure Internet or LAN server. While we do refer to some things you can do to make your system more secure, there are many other measures related to system security that also need to be taken into consideration and they are not covered on these pages.

These guide pages are meant as a learning tool only. The knowledge gained on these pages will help you understand the material covered in security-related publications when you are ready to consider setting up a production server.

Did you find this page helpful ?

If so, please help keep this site operating

by using our CD, gear, or book pages.

Site, content, documents, original images Copyright © 2003-2010 Keith Parkansky All rights reserved

Duplication of any portion of this site or the material contained herein without

the express written consent of Keith Parkansky, USA is strictly prohibited.

This site is in no way affiliated with the Debian Project, the debian.org Web site, or

Software In The Public Interest, Inc. No endorsement of this site by the Debian Project

or Software In the Public Interest is expressed or implied. Debian and the Debian logo

are registered trademarks of Software In The Public Interest, Inc. Linux is a registered

trademark of Linus Torvalds. The Tux penguin graphic is the creation of Larry Ewing.

LIABILITY

IN NO EVENT WILL KEITH PARKANSKY OR BLUEHOST INCORPORATED OR ANY OF ITS' SUBSIDIARIES BE LIABLE TO ANY PARTY (i) FOR ANY DIRECT, INDIRECT, SPECIAL, PUNITIVE OR CONSEQUENTIAL DAMAGES (INCLUDING, BUT NOT LIMITED TO, DAMAGES FOR LOSS OF BUSINESS PROFITS, BUSINESS INTERRUPTION, LOSS OF PROGRAMS OR INFORMATION, AND THE LIKE), OR ANY OTHER DAMAGES ARISING IN ANY WAY OUT OF THE AVAILABILITY, USE, RELIANCE ON, OR INABILITY TO USE THE INFORMATION, METHODS, HTML OR COMPUTER CODE, OR "KNOWLEDGE" PROVIDED ON OR THROUGH THIS WEBSITE, COMMONLY REFERRED TO AS THE "ABOUT DEBIAN" WEBSITE, OR ANY OF ITS' ASSOCIATED DOCUMENTS, DIAGRAMS, IMAGES, REPRODUCTIONS, COMPUTER EXECUTED CODE, OR ELECTRONICALLY STORED OR TRANSMITTED FILES OR GENERATED COMMUNICATIONS OR DATA EVEN IF KEITH PARKANSKY OR BLUEHOST INCORPORATED OR ANY OF ITS' SUBSIDIARIES SHALL HAVE BEEN ADVISED OF THE POSSIBILITY OF SUCH DAMAGES, AND REGARDLESS OF THE FORM OF ACTION, WHETHER IN CONTRACT, TORT, OR OTHERWISE; OR (ii) FOR ANY CLAIM ATTRIBUTABLE TO ERRORS, OMISSIONS, OR OTHER INACCURACIES IN, OR DESTRUCTIVE PROPERTIES OF ANY INFORMATION, METHODS, HTML OR COMPUTER CODE, OR "KNOWLEDGE" PROVIDED ON OR THROUGH THIS WEBSITE, COMMONLY REFERRED TO AS THE "ABOUT DEBIAN" WEBSITE, OR ANY OF ITS' ASSOCIATED DOCUMENTS, DIAGRAMS, IMAGES, REPRODUCTIONS, COMPUTER EXECUTED CODE, OR ELECTRONICALLY STORED, TRANSMITTED, OR GENERATED FILES, COMMUNICATIONS, OR DATA. ALL INFORMATION, METHODS, HTML OR COMPUTER CODE IS PROVIDED STRICTLY "AS IS" WITH NO GUARANTY OF ACCURACY AND/OR COMPLETENESS. USE OF THIS SITE CONSTITUTES ACCEPTANCE OF ALL STATED TERMS AND CONDITIONS.